The Grand Abyss

Abyss — Layer the Fourth

Also Known As: The Blood Rift, the Cesspool, the Everfall

The Nature of Evil: Delve deep, and delve greedily, grab what you can before some other sod does. Expect trouble, for trouble is definitely expecting you. Be prepared, and if you can weaken others while you’re preparing, then so much the better.

The Chant

They call it the ‘Grand’ Abyss like it’s somethin’ majestic. Ain’t nothin’ grand about it, unless you fancy endless cliffs, endless fallin’, and endless bloody misery. Still, if you’re fool enough to go, I’ve got the chant on what to expect…

Now imagine Bytopia, stand it on its end, kill all the plants, throw the petitioners off a cliff, and fill what’s left with some really bad-tempered fiends.

—Voila! describes the Grand Abyss to the clueless

Dividing the Infinite

First things first, berk—the Grand Abyss is a big, gaping chasm that never ends. Not up, not down, and not sideways neither. Call it a “layer” if it makes you feel better, but it’s more like an infinite rift in the fabric of the plane. The story goes that this layer’s the real reason the Abyss is called the Abyss. It’s a yawning hole of infinite depth, an endlessly twisting canyon between opposing cliff walls about a mile apart. Now to a climber it looks less than a mile, but as soon as you leave the rock face and start to cross one of the bridges you realise the Abyss has tricked you and it’s a lot further—and darker—than it looks from the cliff.

Some terminology would be useful at this point. The two solid faces of the Grand Abyss are known as Precipit and Hag’s Rock. Precipit is notorious for the nasty creatures that dwell here who use petrification attacks—basilisk, medusa and cockatrice and the like. It’s the rougher cliff, riddled with side-canyons, gulleys, and waterfalls. On Hag’s Rock, which tends to be more pock-marked with caverns, flocks of vampiric vargouille lurk, preying on fiend and planewalker alike. It also stinks something rotten, what with all the vargouille guano.

Vertically, the Grand Abyss is divided into three regions, known as the Voragos. This part might be hard to get your brain-box around. Closest to Pazunia (although remember there’s no ‘top’) the Upper Vorago is characterised by the rarified air. In the higher canyon the winds are stronger and the smell is reminiscent of sulfurous smoke. The Middle Vorago has more bridges criss-crossing the chasm, and the atmosphere here is thicker and mistier, in places you can’t see the other cliff through the fog. The Lower Vorago is even darker and more shadowy than the higher regions, and it’s notorious for the higher frequency of falling debris, both rubble and petitioners. It’s also rife with webs—particularly around the Venomspire and the gate to the Spiderweb Pits—as enterprising predators try and catch a falling meal.

While the Grand Abyss is thought to be infinitely deep, greybeards reckon that the chasm is only ten miles long, give or take. If a cutter keeps moving along the cliff face long enough they’ll end up right back where they started. What’s even stranger, the canyon’s walls slope slightly inwards, but despite this they always seem to remain roughly the same distance apart. Except where they don’t—and the narrower parts are often connected by bridges. Chalk it up to the mysteries of the planes if you like, because many a Guvner’s tried to explain the weird geometries of the Grand Abyss logically and failed. And a few fell in trying. Nasty business.

The chasm does not have a top—at least on this layer—because you can definitely climb down into the Grand Abyss from the badlands of Pazunia, you just can’t climb back out again. Despite being accessible from Pazunia, the sheer scale of the Grand Abyss—and lack of direct access to the Astral plane—has led the Fraternity of Order to categorise it as a separate layer. As if the Abyss would oblige by being easy to put in such a box.

Now a lot of berks think the Grand Abyss doesn’t have a bottom either, but some planewalkers claim that somehow there is a bottom, or even more than one of them, despite it being infinitely deep. If that makes you scratch your head then firstly: welcome to the planes, and secondly, just think about the Spire of the Outlands.

To be safe in the Grand Abyss you’ll need to keep one eye watching above, one eye watching below and one more watching the cliff right ahead.

—Planewalker saying

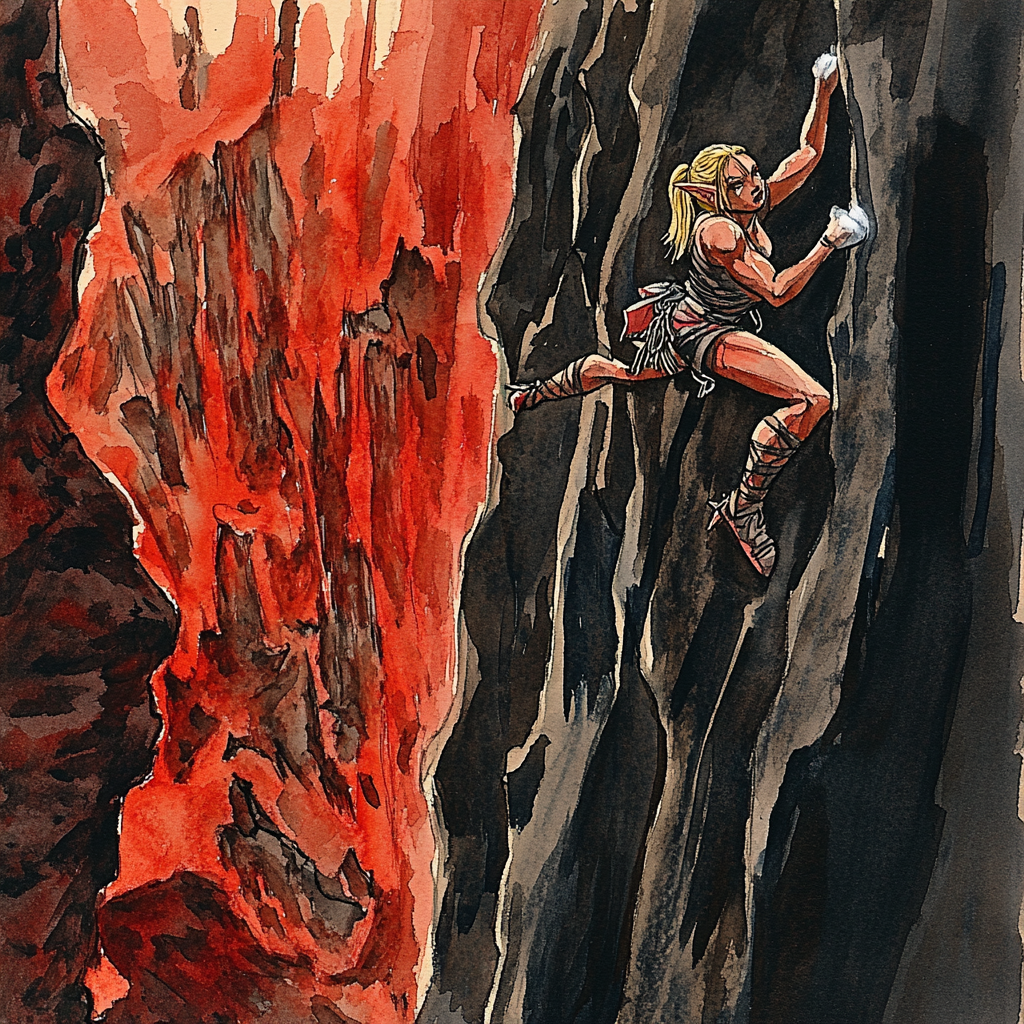

Getting around on this layer is challenging, to say the least. You’ll need to be a confident climber, with a good head for infinite heights, and a grip like Baatorian green steel. The (un)natural cliffs here are irregular, which admittedly makes climbing a little easier, but also jagged, which makes it hazardous if you have fleshy hands. Bring some protective gloves. More worryingly, the rocks tend to fray climbing ropes with alarming speed, almost like the layer wants travellers to fall. I jest. There’s no ‘almost’ about it. Bring spares, or better still, bring enchanted or metallic ropes.

In parts of the Grand Abyss that are populated, you might find handholds hacked into the cliff face or pitons hammered into the rock. Now it depends who made them as to whether it’s a good idea to use these or not. You might have noticed that some of the locals in the Abyss are a little, how should we call it, vindictive. Make sure you’re checking handholds for traps, contact poison and teeth. And test pitons for their security too; it wouldn’t do to rely on a metal spike that’s been deliberately hammered in badly to fool climbers. Or is a small mimic, clinging to the cliff and patiently waiting for dinner to come along?

If you’re really lucky, you’ll find yourself in a part of the layer where cliffside roads have been carved out, or ledges or tunnels. Well, you’re lucky in that it makes climbing and resting a little easier, but there’s a limit to the luck—because it also means you’re probably in the territory of who or whatever carved the trail, and it’s a cert that they want to eat you, or at the least push you off. Use these paths with caution!

Welcome to the Abyss. Mind the gap!

—Planewalker saying

Gates and Bridges

Now don’t go thinking this layer’s just a big pair of cliffs, basher. On both of the faces dwell isolated battalions of tanar’ri and their worker-slaves. These poor berks spend their afterlives digging out fortifications from the hard rock walls. Their efforts have been going on for a long time, evidently, for in some places the Grand Abyss is almost cluttered with walkways, staircases and ledges constructed from the solid rock. You can even find delicate arches that cross the chasm at strategic narrower points, some of them magically fabricated, others made by accident or by the layer itself, especially where there are gates that travellers want to access.

Ah yes, the gates. They are, after all, why anyone comes here in the first place. Like Pazunia, which is pock-marked with pits containing gates to deeper layers of the Abyss, the Grand Abyss has more than its fair share of gates too. Here though they appear more like portals in the cliff faces, some of them obvious, some of them hidden. Many are permanently active; just walk through the shimmering surface with confidence and you’ll emerge in whatever godsforsaken hell-hole it’s connected to. Others work more like portals, requiring a key. Oh, and many are guarded, sealed off or otherwise barricaded. To control the gates is to control travel in the Abyss, and that kind of power is just too tempting.

- The better known landmark bridges are described here

- You can learn the dark on particular Grand Abyssal gates here

Come Fly with Us

Sod climbing for a lark, I can almost hear you splutter. That sounds like too much hard work, and dangerous too! Well, you’re not wrong, but the obvious alternative—flying—is certainly not without its own hazards. Firstly, be sure to check the weather before launch. Here in the Grand Abyss it’ll be far more sinister than you’re used to for sure, learn more about the weather here.

You’ll also need to watch out for lurkers; there are plenty of predatory monsters that dwell in natural or artificial caves and crevasses in the cliff edge, waiting for dinner to fly or fall past. Some are jumpers, launching themselves out to catch prey and then glide or fly back to their lair. Others are web-hunters, and have spun strands across the chasm to snare their lunch. And some have exceptionally long and sticky tongues and blindingly fast reflexes. Basically, be wary of attracting too much attention by flying.

At the same time, however, rubble constantly falls from mining operations further up the rock face (and remember, berk, as the plane is infinite, there’s always someone higher up!), which can damage constructions and knock unlucky berks over the edge to endlessly tumble down.

The Locals

The as well as the lurkers, the rock faces are the territory of some pretty vicious creatures. That’s as well as the tanar’ri, berk! On Precipit you’ll find basilisk and cockatrice, as well as the occasional nest of medusa. On Hag’s Rock, all manner of vargouille infest the caves and terrorise tanar’ri and humanoid alike.

The afterlife of petitioners here is brutal, and often short too. They usually ‘arrive’ on the layer rapidly and vertically—yes, cutter, they start by falling. The Abyss’ idea of a joke, presumably. Some might end up falling for days, or even years, if they appear near the centre of the chasm. The unlucky ones get blown into the cliff face by the ever-present winds and meet grizzly ends. The really unlucky ones survive somehow, and then end up desperately clinging to the cliffs, vulnerable to the elements and predators.

More on the petitioners of the Grand Abyss here

The Visitors

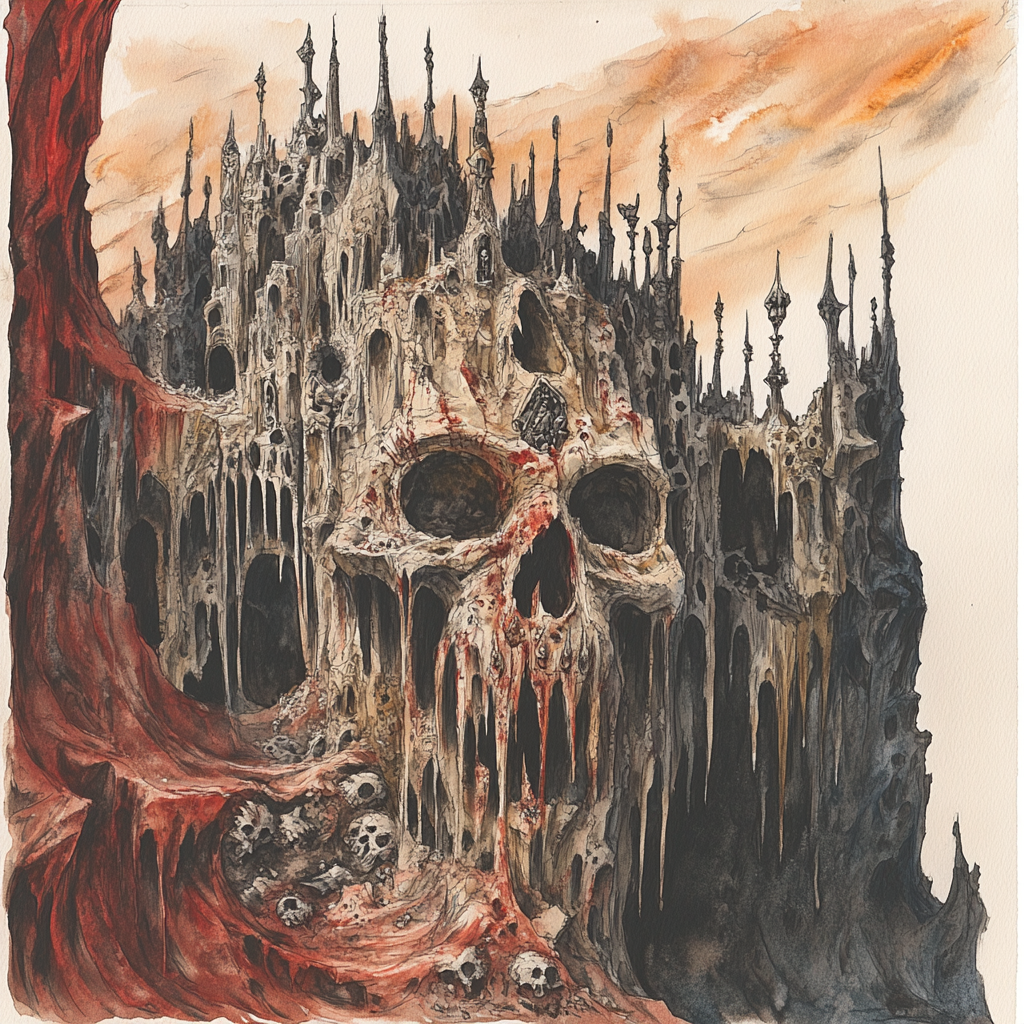

The tanar’ri high-ups who stake their claim in the Grand Abyss are the sort who see danger as a challenge, not a deterrent. These are the warlords, lieutenants, and self-styled “princes” of the Abyss—not quite archdemons, but certainly with the ambition to be. They carve out their citadels with brute force and borrowed hands, commanding armies of miserable slaves to chisel the cliffside. Their fortresses hang like scabs on the wall of infinity, jagged and sharp, always half-finished but rarely abandoned. Chant goes they’re trying to fortify the place against a baatezu attack, that might never come. Black iron walkways twist like intestines, and half of them lead nowhere. Every fortress is a gamble against catastrophe—one rockslide, one betrayal, and it all comes crashing down. But that’s the point, ain’t it? If you can rule here, you’ve proven you can rule anywhere. The overlords watch their subjects with careful eyes, knowing full well that ambition is contagious. And if a rival tries to seize their hold, well, as the saying in the Grand Abyss goes, “gravity is the best executioner”.

Then there are the rank-and-file tanar’ri— the horde, the grunts, and the drifters. For them, the Grand Abyss is just a shortcut through the infinite. Why carve a path through a dozen separate layers when you can take a perilous plunge through the Everfall instead? They leap from ledge to ledge like carrion birds, skitter down twisted stairways, and scuttle over rotting rope bridges strung together by whatever barmy soul last passed this way. The smarter bloods carry hooks and chains to swing from ledge to ledge like crazed spider-monkeys. The stupider ones just jump. No maps, no guides—just demonic instinct and luck. Those that misjudge the leap are claimed by the fall. Every abyssal denizen knows the sound of a falling tanar’ri: the guttural scream, the long silence, and the faint splat that eventually echoes back up as they bounce off an outcrop o a bridge.

Falling is the tax you pay to take the fast route

—Planewalker saying

And then there are the planewalkers, wide-eyed fools and wild-hearted veterans alike. Some of them are looking for adventure—mostly they’re addle-coves with too much courage and not enough sense, hoping to be the first mortal to chart a new gate or find a new layer in the Chasm. Others have no choice. Maybe their portal led them to a ledge with no obvious way out. Maybe they’re fleeing a pursuer. Whatever the reason, planewalkers tend to tread the Grand Abyss like tightrope-walkers with more confidence than they have balance. The Chasm gobbles up the proud and spits out the reckless. The survivors learn the Tricks—how to wedge pitons into the treacherous stone, how to spot a false ledge, how to gauge the wind before a jump. But the Abyss is always dreaming up new ways to kill berks. Maybe the bridge gives way. Maybe a chasm-stalker sees you dangling like bait. Maybe a tanar’ri warlord takes offence that a planewalker had the gall to use their ledge. For planewalkers, travelling the Grand Abyss is a test of how much you’re willing to gamble.

A Brief History of the Grand Abyss

Chant goes that the Grand Abyss began as a bold experiment—ended as a cataclysm that reshaped the Abyss itself. In the early days, demonkind stuck close to the Plain of Infinite Portals, prodding at its noxious pits and clawing their way down to uncover its mysteries. But for the impatient, this cautious approach was maddening. The more ambitious demons wove spells to drill through the bowels of the plane itself, hoping to bypass the chaotic portal network entirely. What they got was disaster on a cosmic scale: the Plain heaved, the skies bled, and a dozen mighty obyrith lords were swallowed in a blast that still resonated through the lower layers of the Abyss. When the poison dust settled, however, what was left was a rift of incomprehensible scope, its walls riddled with gates oozing like wounds which led to countless ‘new’ Abyssal layers. The denizens called it the Grand Abyss, and delved greedily seeking opportunity—and finding peril.

The obyriths, ancient and arrogant, saw the vertical crevasse as easier to defend than an open plain, and they claimed its ledges with spiked fortresses and crumbling bridges. Their ruins still cling to the cliffs today, monuments to a lost age of hubris and tyranny, though there are many false stories about the origin of each structure.

Some greybeards whisper of a different genesis for the grand chasm, one born not of deliberate magicks but of primordial violence: the fabled duel between Demogorgon and Obox-ob, a mythic clash that tore open the Abyss itself.

Whether truth or myth, the rift remains a scar upon the plane. Over its long and blood-soaked history, the Grand Abyss has become a roadway of ruin, offering a tempting shortcut between Abyssal layers for those reckless or desperate enough to use it. Its gates often lead to subterranean lairs, dripping galleries, or hidden caverns deep within other layers, but be warned—the final destinations are prone to shift with the whims of the plane, making maps of the layer chancy at best, even if you were to trust the vendor. Many gates are heavily fortified at one or other end, watched over by chained beasts or scheming demonic guardians who would sooner kill than offer safe passage.

Digging Deeper—Chant of the Grand Abyss

- Bridges of the Grand Abyss — being the safest way to cross the grand chasm‡

- Gates of Renown — being a survey of the better-known gates of the Grand Abyss‡

- Petitioners of the Everfall – being an exploration of the kinds of sinners who end up here for eternity‡

- Weather in the Grand Abyss — being a warning of the weird and dangerous climate of the layer‡

Locations in the Everfall

- Abyss of Ragnarok, the (realm of Nastrond)‡

- Bastion of Thorns (fortress of Laraie)‡

- Bitelbrouw (burg)‡

- Blood River (site)

- Bridges of the Grand Abyss‡

- Black Lattice (site)

- Bridge of Teeth (site)

- Bridge of Trepidation (site)

- Brittle Bridge (site)

- Chainwail (site)

- Flayed Bridge (site)

- Veinspan (site)

- Cesspool, the (site)

- Citadel Insectivorae (Doomguard base)‡

- Citadel Maw (Doomguard base)‡

- Citadel Svart (Doomguard base)‡

- Clinging Forest, the (site)‡

- Dol-Moroth (burg)‡

- Gates of Renown and Infamy‡

- Agonising Doorway (to layer 12)

- Blistering Door (to layer 403)

- Bramblegate (to layer 377)

- Carapace, the (to layer 663)

- Cesspool Gate (to layer 400)

- Copper Wound (to layer 113)

- Devouring Door, the (hazard)

- Clock Without Numbers (to layer 121)

- Door of Many Names (to layer 71)

- Doorway To Obliteration (to layer 531)

- Fissure of Bones (to layer 112)

- Forbidden Gate, the (to layer 68)

- Furnace of Hearts (to layer 45-47)

- Gallows Arch (to layer 109)

- Gate of Dancing Chains (to layer 57)

- Hallucination Gate (destination unknown)

- Hungerer, the (to layer 10)

- Laughing Arch (to layer 600)

- Lychgate, the (to layer 16)

- Maw of Klesh’gorr (to layer 136)

- Mirror that Bleeds (to layer 487)

- Pathless Gate (to layer 444)

- Rusted Keyhole (to layer 270)

- Screaming Key (to layer 222)

- Scuttling Tower, the (to layer 2)

- Six Tricks (to layer 176; hazard)

- Stitched Gate (to layer 467)

- Stone That Weeps Blood (layer 103)

- Tinea Corporis (layer 222)

- Thorn-Crowned Mirror (layer 49)

- Two-Faced Gate (to layer 93)

- Veil of Swarming Glass (layer 66)

- Whispering Fissure (to layer 3)

- Gilded Spires (fortress of Graz’zt); gate to layer 46‡

- Granite Spur (burg)

- Hanging Gardens, the (site)‡

- Morglon-Daar (burg at the edge of the Grand Abyss)

- Pale Ossuary (former fortress of Zanatose)‡

- River Pyriphlegethon (planar pathway)‡

- Sepulchre of Mydianchlarus (site)

- Singing Falls (site)

- Six Tricks (gates to layer 176; hazard)

- Styxfalls (planar pathway)‡

- Tumulus of Abhorrence (site)

- Venomspire, the (temple to Lolth)‡

Cutters of Note

The layer has no single ruler.

- Ardat the Unavowed (three-headed harpy abyssal lord)

- Asima (Abyssal lord — deceased)

- Guardian of the Gates (planar klurichir [he/him] / CE) — Fiendish Codex 1 [3e] p133

- Jarn Klythe, Scribe-Executor (Fraternity of Order planewalker)‡

- Krytharion the Husk (Doomlord of Citadel Insectivorae)‡

- Liriel Dendrin, Archivist-Magistrate (Fraternity of Order planewalker)‡

- Mortrana, Lady (leader of the Morthbrood)‡

- Nastrond (power of the apocalypse)

- Olrakil (planar lilitu tanar’ri [she/her] / Society of Sensation / CE)‡

- Seventythree, Blade-Archivist (Fraternity of Order planewalker)‡

- Sorraskh (planar wastrilith tanar’ri [she/her] / CE)‡

- Trobbo-gotath (planar tanar’ri / CE)

- Velyndra Xil’quess, Matron (drow high priestess of Lolth)‡

- Vex the Unraveller (Doomlord of Citadel Svart)‡

- Vynra Thal, Adjudicator (Fraternity of Order planewalker)‡

Philosophies of the Grand Abyss

- Edgewalkers (nihilistic survivalist sect)‡

- Inquisition of Interdiction (Fraternity of Order planewalking organisation)‡

- Morthbrood, the (apocalyptic sect)

- Soul Sirens, the (harpy organisation)

Bestiary of the Grand Abyss

- Aeshar‡

- Basilisk

- Cockatrice

- Elf, Drow

- Harpy

- Medusa

- Mehrim (goat demons, 5e stats)†

- Mimic

- Nalfeshnee

- Schir (spite demons, PF1 stats)†

- Tanar’ri, any

- Trolls, Mummified

- Vargouille

- Verdant Reaper (aconalith tanar’ri)‡

- Vrock

- Yochlol (handmaiden tanar’ri)

Canonical Sources

- Demonomicon [4e] p50-57 (called the ‘Blood Rift’)

- Fiendish Codex 1 [3e] p109-110,116,132-133,155-156

- Planes of Chaos [2e] Travelogue p11

- Dragon Magazine #353 p37; #359 p47 — brief mention

- Dungeon Magazine #148 p56 — brief mention

Other Sources:

- Layers of the Abyss — material adapted from the excellent netbook authored by Eli Atkinson, Will Church, Serge W. Desir Jr., Marley Sage Gable, John Harris, Sam Peer, Adam Silva-Miramon, Sean Surface

- Jon Winter-Holt.

- † denotes third party content, ‡ denotes homebrew lore.